“Softness Is a Power:

Astria Suparak in Conversation with Dorothy R. Santos”

X-TRA CONTEMPORARY ART JOURNAL

Spring 2023 issue, Volume 25 Number 1

http://www.x-traonline.org/article/softness-is-a-power-astria-suparak-in-conversation-with-dorothy-r-santos

Excerpts:

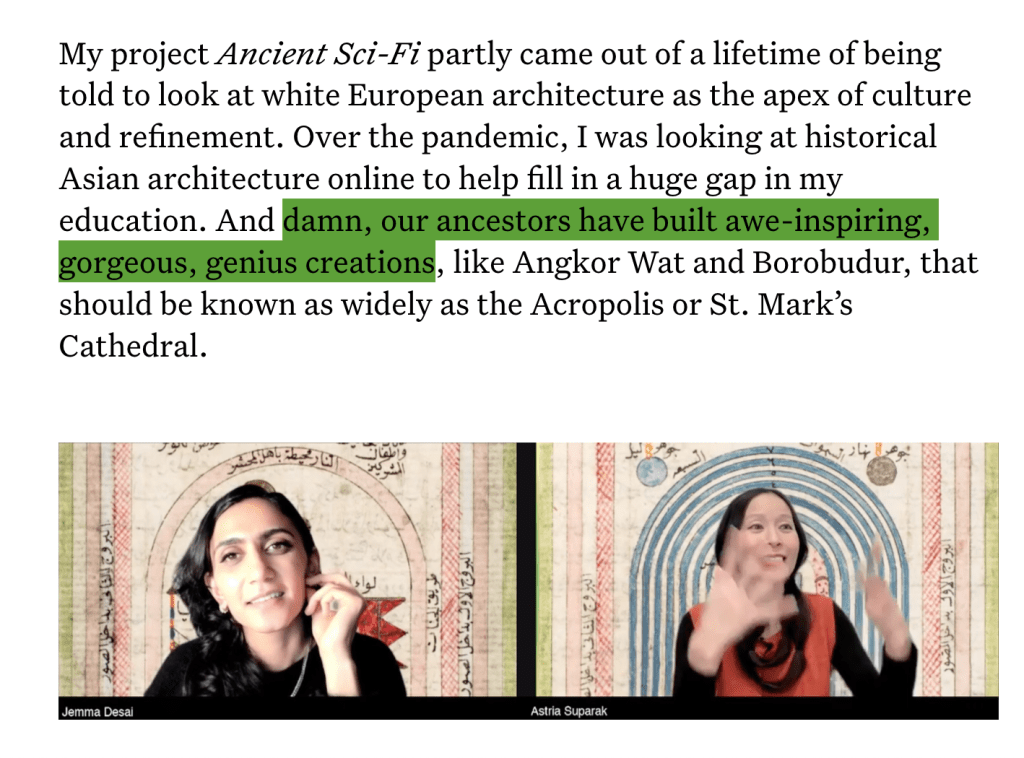

In Astria Suparak’s ongoing multimedia performance Asian futures, without Asians, the artist argues that science fiction is not a modern invention descended from the imagination of the West. Instead, she presents Asian cultural materials from across six centuries that feature concepts—such as eternal life, astrology, divination, and the apocalypse—and motifs—the cosmos, magical and mythical creatures, and deities—intrinsic to present-day science-fiction and fantasy.

Suparak made virtual backdrops for her performances of Asian futures, without Asians using a different Asian cultural artifact for each venue. Her artist’s project for X-TRA, Ancient Sci-Fi, comprises limited-edition posters based on these backdrops. Each printed copy of the issue includes one of the four designs. These backdrops are also available as digital downloads on our website.

In the conversation that follows, Suparak and the writer and artist Dorothy R. Santos discuss Suparak’s ongoing scholarship, which, in addition to researching historical Asian artifacts that presage contemporary concepts of sci-fi, catalogs the appropriation of Asian objects and tropes in mainstream sci-fi films and television.

DOROTHY R. SANTOS In rereading your work, Asian futures, without Asians, I was reminded of your cultural and anthropological excavation of the more than sixty sci-fi films and TV shows that you included in your research. I witnessed the first iterations of your work for the Wattis Institute publication Why are they so afraid of the lotus?, which was focused on Trinh T. Minh-ha’s films. In that piece, you say: “Asian as a costume, a temporary skin, a vacation. An eccentricity, an indication of rank, and a means of self-discovery.” Clearly, there’s some clever tongue-in-cheek happening here, as if one needs to be overtly absurd about an identity, a people, a person serving as a proxy for objects and signifiers! Clearly, an Asian is not a costume or a skin, but Asian is used as a stand-in for something abstract and rather difficult to explain happening in the world. For instance, you astutely point out Alexis Rhee, a Korean American, playing a geisha in an advertisement within the backdrop of Ridley Scott’s 1982 Blade Runner. Her figure serves as a stand-in, both literally and figuratively; the director invokes her likeness as a way of speaking on behalf of, as opposed to what Trinh’s work encourages us to do: to “speak nearby.”1 This method of speaking nearby might prevent these blatant forms of cultural appropriation and misrepresentation. Rhee’s visual presence becomes a part of an American imaginary that is extremely difficult to undo, unsee, and unlearn. Yet it serves as a looming presence.

You branched off after Why are they so afraid of the lotus? and started to create other multimedia works focused on various related themes and tropes, even nonhuman mediations. (I’m thinking of For Ornamental Purposes [2022].) I’m curious how the work you developed during our time at the Wattis has expanded and led to other artworks and projects.

ASTRIA SUPARAK The whole Asian futures, without Asians series started as research for that visual essay for the Wattis book. I was so enthralled by the research—culling imagery from dozens of mainstream science-fiction movies and TV shows, and writing well beyond the word limit—that I also developed a multimedia presentation that I’ve been touring with for the last year. It was originally going to be performed in person in San Francisco, but we had to postpone and then move it online because of the pandemic. The Ancient Sci-Fi (2021–22) backdrops were designed for the performance, with a different Asian cultural artifact for each venue.

At an hour long and stuffed with over three hundred slides, the presentation was still not enough to contain the rabbit holes I journeyed into while researching and making the essay and lecture. I’ve expanded some parts into other projects, like a visual essay and collage on the Asian Conical Hat trope. And I’ve made new work for things that didn’t fit, like the Tropicollage (2021) video and Aloha, Boys (2022) wall piece, on how the tropics are fetishised. Some of the slides in the presentation are collages of images of the most persistent tropes, and I’ve made murals and installations based on these, such as Sympathetic White Robots (2021–22) and Tang Rainbow (2022), on Chinese-ish costumes seen across half a century of white-made sci-fi. I also made GIFs for the presentation, which I’m trying to figure out how to include in other works, for example, the koi in For Ornamental Purposes.

Virtually Asian (2021) is the penultimate section of the presentation—a trope I call Giant Geisha Ads—which I turned into my first short video. It is a stand-alone work and also slots into the performance.

[…]

SANTOS In the spirit of Saidiya Hartman’s concept of critical fabulation, I’m also curious about your specific methodology of searching for meaning in specific symbols and artifacts through their historical and cultural contexts.4

SUPARAK It’s not so much fabulation or searching for meaning, necessarily, but maybe looking for signs of reification? Interpreting how these artifacts and concepts are being used in a white Western context, and then developing a critical response that addresses the ahistorical use of these specific, and sometimes non-specific, Asian imageries and ideas.

My process for this research started with watching a ton of sci-fi and screen grabbing any element I recognized as or suspected was Asian—inclusive of East, Southeast, South, Central, and West Asia. I organized them into categories, and the recurring elements then guided my research, leading me to more areas to look into. This included many histories and cultures I wasn’t as familiar with, and eventually, I connected with outside experts to double- and triple-check cultural, religious, and language details with people of those cultures and religions and/or experts in those areas, including fashion historians, architects, and martial artists. I did this in order to better understand the objects, names, and customs represented and the significance of how they were being appropriated and stripped of their cultural and historical specificities in the interest of creating a dystopian future for white protagonists.

Beyond the usual historical/cultural/museum sources, I’m also reading and listening to interviews with film directors, production designers, art directors, costume designers, and even the linguists who invent alien languages, and I’m delving into platforms like fan sites, military wikis, and weapons forums.

Building this taxonomy is a way to retrain one’s viewing habits. I’ll often go back to a film to pull a better still, a better clip, or tweak the subtitle settings, once I’ve figured out what I need, and find more objects or tropes I didn’t catch the first time. I can’t watch a film anymore without clocking a Buddha figurine in the background, no matter how blurry!

SANTOS I want to go back to something you touched upon earlier that I haven’t been able to stop thinking about: Fidelity! Your response regarding “dropping a line of inquiry” due to illegibility. There’s a double meaning, maybe even a visual double-edged sword, with the low resolution of these images. It seems that many of these artifacts, especially when mediated through film or digital media (whether through some form of digital photography or in post-production), serve a dual purpose. In one sense, cultural objects or elements are sprinkled throughout media to provide what scholar Koichi Iwabuchi calls a “cultural odor.”5 Your work forces the viewer to question how much an object resembles the country from which it allegedly originates. How much of the object you are examining resembles or is connected to the place it ought to represent? In another sense, the other side of an object’s mediation rests with the viewer and their willingness to either accept or question the way an object is mediated. Herein lies the responsibility of the filmmaker and artist!

I’ve always understood your work and scholarship as a way of encouraging individuals to put in the work to understand the way that something is created, designed, and then wielded as a part of the visual language and how those signifiers start to seep into both individual and collective consciousness and imagination. Taking all of this into consideration, are there films, television shows, or performances that you feel do an excellent job of striking the balance between honoring historical and cultural lineages without being appropriative— works that are imaginative, forward thinking, and speculative in a way that is generative?

Read in full at: https://www.x-traonline.org/article/softness-is-a-power-astria-suparak-in-conversation-with-dorothy-r-santos